A product roadmap is one of the most critical artifacts that product managers create and own. It’s what it says on the tin – an outline of all the necessary steps on the road to achieving a specific end goal or objective. Roadmaps contain a list of product features, enhancements, or campaigns that will drive the product’s evolution. Teams use them to remain on track and meet short- and medium- term product goals, while giving stakeholders oversight to communicate progression.

While roadmaps are undoubtedly important, a common confusion amongst product teams is to mistake a roadmap for a product strategy. A strategy is much more high-level and long-term, honing-in on what the product hopes to achieve in the wider business context. It takes company objectives into account, and defines each activity needed to be completed to ensure those objectives are met. Everyone involved is aligned to maintain a well-oiled machine.

To eliminate blurred lines, let’s clear up what makes product roadmaps different to product strategies, and think about the steps product managers should take in building a successful, coherent product roadmap.

Product Roadmaps Are Ever-Evolving

Product roadmaps often have shorter time scales (9-18 months) when compared to a product strategy, to allow for sudden changes in direction. Let’s say a team has a certain feature expected to be delivered in Q3, but they find it actually doesn’t solve their customers’ problem during an experiment in Q2. The feature has to be dropped. The roadmap has to change. A product strategy is less susceptible to sudden change, as it’s derived from the wider business strategy. Therefore, a change in how a feature is built, or whether it’s built altogether, does not impact the product strategy.

Roadmaps Give Perspective to Stakeholders

Directional in nature, product roadmaps call out different features and make them known to stakeholders (especially senior leadership teams). The product manager uses the artifact - usually bucketed in quarters or months - to signal a potential delivery period rather than committing to a time. Socializing a product roadmap with the wider team, before circulating it across the organization, leaves less room for errors.

Product strategy on the other hand, does not account for feature level details. Instead, a product strategy document focuses on the goals that the product aims to achieve. These goals are in line with business or customer problems that the organization is trying to solve. While a product strategy document also gives stakeholders perspective, it usually doesn’t call out a timeline.

Developing a Product Roadmap is More Difficult

There’s a lot of blanks to be filled at the time of building a Minimal Viable Product (MVP). It’s also difficult to grasp the development team’s velocity, marketing and regulatory hurdles, the potential for scope increase (or decrease) and potential customer reaction towards your product. All these factors have a huge impact on how easily your product roadmap comes together.

Product strategy is less ambiguous. Since the product strategy is focused on providing directional information to solve business or customer problems, the document is written such that product development teams can use it to understand the boundaries of where their digital product fits, and then use it to derive features for that product.

How Can Product Managers Build a Product Roadmap?

Roadmaps can vary between products and teams. However, a common aspect o every product roadmap is a feature backlog. To build a product roadmap, the product manager uses the strategy document and many other artifacts, interviews, and workshops to better understand the problem(s), users, stakeholders, market and technical feasibility. The product manager comes up with a list of features that will help solve the business or customer problem, and offer an enhanced user experience (especially for digital products). These features are then ranked in terms of importance, and that ranking forms the foundation of the product roadmap.

The roadmap for a new product will be less defined, but usually has a set of features bucketed for the first iteration of the product – the MVP. The assumption is that users need a minimum set of features to solve the primary problem. Often product managers go beyond the minimum feature set because they need to build a product that’s marketable, so they can compete and acquire users. In that case, the MVP is not an MVP, but a Minimum Marketable Product (MMP). For new products, once the first set of features are bucketed for initial iteration, the next set is more thematic with a focus on features achieving a certain goal. This is repeated in the third iteration as well.

For existing products in the market, roadmaps are a little more defined. The product manager can use data – produced through customer feedback, product analytics tools, competition landscape and market changes – to define the roadmap. Additionally, they also have a good idea of the team’s velocity in indicating potential time for delivery on the roadmap.

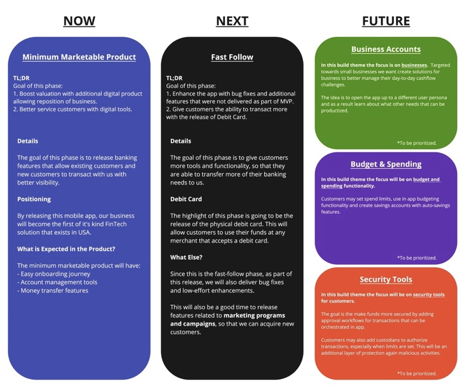

I’ve had the opportunity to work on several new products (and respective roadmaps), using a ‘Now – Next – Future’ model. This approach allows me to communicate to leadership and other stakeholders what product delivery could look like, without specifying time period. For new products, the roadmap is usually defined as part of product planning process. During this time, it’s often not possible to get true estimates, especially because the engineering team isn’t formed or allocated. It’s likely that there’s a solution architect and/or tech leads involved in the planning process, but they alone cannot provide true delivery estimates and usually provide more high-level, t-shirt size estimates. This is why I break down the roadmap into the ‘Now – Next – Future’ format.

Here is a sample of such a roadmap. This roadmap is very thematic in nature and doesn’t have the feature level details.

When you’re building a roadmap for existing products, it‘s not unusual to uncover and unlock new opportunities for your product. Sometimes these are new features, other times enhancements to existing features, but often, these opportunities are just improvement to user experience in your digital product. This will change the roadmap quickly as the importance ranking of features will shift based on real data from customer feedback.

Roadmaps, especially those for products already in the market, should be validated by engineering leads or solution architects. As indication of delivery time is communicated through the roadmap, it’s important that there’s buy-in from the engineering team - since they’re the ones that’ll build the product.

Here’s a sample of a roadmap for an existing product. This calls out specific features and is built to indicate to stakeholders times when the team is doing product planning work and times when there’s development work happening towards the features called-out.

The product roadmap and product strategy are two very different things. Roadmaps aren’t a substitute for a strategy document. Instead, they’re complementary artifacts whereby the roadmap is in support of the strategy, providing more detailed context of how a product development team will deliver on the defined strategy.